|

Online Store Directory

Spiritual Meditations and Exercises

Who We Are and What We Teach

Brotherhood of Light Lessons: Course Books on Astrology, Alchemy and Tarot

Astrology Software

Calendar of Activities

Astrological Sunday Services

Church of Light TV

Classes

Quarterly

Support Us

|

Serial Lesson 159

From Course XIV, Occultism Applied, Chapter 9

Original Copyright 1944, Elbert Benjamine (a.k.a. C. C. Zain)

Copyright 2011, The Church of Light

Subheadings: False Standards Mental Breakdown Egotism and Alibis Conservatism and Radicalism The Precious Child Inferiority Complex Shyness Over Sensitiveness Boasting Summary of Emotional Reactions What Brings Honors Pleasing the Boss Prepare to Fill a Better Position Character Advertising Occult Considerations Demonstrating Honors

Birth Charts: General Eddie Rickenbacker Chart Faith Baldwin Chart

Chapter 9

How to Achieve Honors

THE driving force of modern industry is self-respect and the respect of others. The reproductive urge and the urge to seek food are fundamental; but modern man encounters no great barriers in the way of finding a mate and satisfying his hunger. In the matter of satisfying his self-esteem, however, the rising standards of living cause his family and his associates to expect increasingly greater results from his efforts.

Self-respect has come to be the most vital factor of human life. It resists attack and invasion more strongly than any other urge, even than the urge for life itself. One way to maintain and increase it is to gain the respect of others. Whether he realizes it or not, everyone desires at least to be worthy of honors.

When I say that the respect of others is a driving power in our economic relations I mean that Harry or John might loaf in the shop were it not that other workmen would consider him lazy and thus inferior. Sam Smith, the crack salesman, would be content to earn $10,000 a year, except that his wife wants a new home and expensive clothes, so that she may feel socially equal to Mary Jones. So Sam steams up and increases his sales to an income of $20,000. Likewise, the janitor’s boy wants to go to college because his pal is going, and his father asks for a raise, or gets a new job at larger pay, so he can send him. People could live without these things, but they would not gain the same respect from others.

Back of this desire for the esteem of others is the ego ideal. That is, each individual as he develops from infancy comes to look upon himself in a certain way. Gradually he acquires standards of conduct. Because others seem to expect certain things of him, he comes to expect these things of himself. Or, on the other hand, because he fails to do what others expect of him, and receives their censure, he may look upon himself as a failure in certain ways.

Experiences modify his view of his own character. The suggestions of other people have an effect. In fact, all he thinks and does, as well as all that happens to him, have an influence. The result is that as he grows to maturity and his opinions stabilize he has pretty definite ideas of his own abilities, his own worth, and just about what he expects of himself under various circumstances.

This idea of himself which every person holds may, or may not, represent the real character. It may, or may not, rest upon ideals which are sound, and which are possible of realization.

The emotional elements that enter the life during infancy are powerful to warp these self-ideals. The experiences of youth also contribute emotional elements that may have drastic power. Not only the teachings of elders, but their example, give direction to these mental images that shape the conduct in after life. They are the conceptions by which the child attempts to adjust himself to the situation he confronts. Because of the limited experience and wisdom of the child, all too often some of these conceptions are based upon fallacy. When so founded they nevertheless persist, and influence the conduct profoundly even in adult life.

In learning how to achieve honors, therefore, our first task is to examine our standards of value. Growing from infancy to maturity we have all been faced with many situations which we were not fitted by experience adequately to understand. As a consequence, the importance we attach at the time to some of them was disproportionate. Perhaps at present we would view these situations differently, but the inexperience of childhood caused us to react to them with undue emotional emphasis. And having, in later life, forgotten all about the occurrence, we have never taken the pains to make an emotional readjustment to these experiences of childhood, and properly revalue them.

Human relations are so complex, and some of them so recently developed as seen from a biological standpoint, that there are a multitude of ways in which the emotional responses of a child may be given an unusual bias. Few there are of us, therefore, who grow to maturity without some emotional twist that under certain circumstances makes us seem queer or at least not perfectly poised. And some of these emotional biases are of such proportion as to make adequate adjustments to life as we now find it very difficult.

If we are to achieve honors we must render valuable service to society through the development of our personal prowess to a degree of superior efficiency. Unusual emotional reactions to, or unusual valuations of, the incidents arising from our work and our human contacts, are great and often insurmountable handicaps. Let us, therefore, examine how a few of the most common arise, and how readjustment may be made.

False Standards

As a result of the example of our associates, their admonitions and suggestions, and our own experiences, from the earliest infancy we built up an opinion of just what we expect of ourselves under various circumstances. We have ideals, and these ideals should be high. They cannot be too high; for they are the goals toward which we work. Should we reach them they are no longer ideals, but facts.

But in addition to ideals we have standards. These standards are not merely ideals but are what we actually expect of ourselves in the way of more or less immediate performance. Such standards may be sound or they may be false. When they are the latter they give us no end of trouble.

Very frequently a person sets himself a standard that is to him impossible of attainment. Various types of neurotic diseases, for instance, arise from a conflict between the fundamental urges of sex and false standards of purity. The person has set himself a standard that does not permit even a thought of sexual expression. His biological heritage demands this expression. But he has so firmly established his standard in his own mind that his objective consciousness is totally unaware of the existence of the, to him, objectionable desire. But though he is quite unaware of its existence because he represses it, it does not cease to exist. And like every energy not finding a legitimate outlet, it finds a substitute outlet, and manifests as one or more of a score of diseases which can only be relieved by acknowledgment of their source.

This particular type of false standard has become widely recognized through the Freudian literature. But it is only one of numerous types. Another of these was responsible for the death of a man of unusually fine character and a very dear friend. The case, as is customary, dates back to childhood. He was a child of well-to-do and highly respected parents in the Middle West. Financial success, next to an honorable life, was the family standard. He was brought up under the impression that great things were expected of him in a financial way. Before he was twenty he came into possession of some money, went to Chicago, and speculated on the Board of Trade. For a time he had remarkable success, then began to lose. Before he had lost all, he left Chicago and invested the remaining amount in a transitory business enterprise. In this he was amazingly successful. Still under twenty years of age he was considered by his friends a financial wizard.

He then went into real estate and other enterprises. No business was attractive to him unless it held opportunities for big gains. But instead of big gains he steadily lost. Year after year saw his funds dwindle. He had ability to make a moderate salary working for others; but the image of himself created by his family in childhood, and intensified by his great temporary success, would not permit him to be anything but a grand financial success.

Yet the standard he had set for himself was beyond his reach. While he still had money enough to be considered fairly well to do, he began to deem himself a failure. He developed a chronic sigh. He worked persistently and struggled courageously to gain the fortune which he considered was his right in the world. Not until every possibility of making the fortune he had in mind seemed closed did he give up. When finally he realized there was no hope of realizing his standard he died. He died not of any physical ailment, but a martyr to an impossible standard of achievement.

A more commonly observed instance is that of a child whose parents and their associates believe and perpetuate the idea that he is just the smartest thing in the world. He is taught to believe that everything he says is of unusual importance and that in some manner he is superior to other children of his age. He grows up an egotist, but the time is finally at hand when he must face the stern realities of life. In open competition he tries to make his way in the world, but just does not seem to get ahead. He knows that he has more ability than others who receive the promotions, because has he not always been told that he is smarter than others? He feels therefore, that he is ill-treated, and that those over him do not appreciate his qualities, when as a matter of fact he is receiving just consideration. This fallacy as to his own worth, implanted in childhood, under these conditions gives rise to a mental conflict. He chafes at not receiving what he considers his just dues, or if the conflict becomes acute he suffers a mental breakdown.

Mental Breakdown

A mental breakdown, as distinct from the rare organic diseases of the brain, is always caused by a conflict between mental factors. We see it exhibited in a mild form by the individual who has set standards (not ideals) for himself just above his reach. When he plays a game of golf, perhaps a good game, he expresses astonishment that he should play so poorly, and shows irritation or marked depression when he makes a bad shot. Or in the conduct of his business if he makes some minor error, he shows that he is quite upset about it. Such an individual, everywhere common, has established a standard of perfection for himself which is foreign to real experience. The conflict between his real self, his real performances, and these false standards are a cause of recurring emotional disturbances. These detract from his real efficiency in life.

Mental breakdown is not confined to the human family. Pavlov, in his experiments upon dogs, found that he could induce neurasthenia in them. First he would set problems for a dog that were not difficult, by the solution of which he could reach food. From time to time new problems, in the way of opening doors, etc., would be set, but still within the mental ability of the dog to learn and perform. Then, after the dog’s confidence that he could reach the food by solving a problem was built up, Pavlov would present a problem so difficult that the dog could not solve it. Under these circumstances the dog would fret and worry day after day until he was in a state of nervous exhaustion. Finally he would begin to act strangely, to be irritable, to start at every sound, to bay at the moon, to refuse to touch food given him, and exhibit all the symptoms of a complete mental disarrangement.

No one should be content with performances less than his very best. Everyone should have an ideal above and beyond anything he has so far accomplished, toward which he should resolutely struggle. But one should always feel satisfied with one’s best. Not to do so indicates that there has been unsound valuation of one’s abilities. And any resulting emotional perturbation is uncalled for mental conflict that consumes energy and if extreme may lead to complete mental breakdown.

Pavlov, who won the Nobel prize in 1904, learned just how conflicts between mental factors within the human mind lead to neurasthenia, and may lead to insanity, through setting up parallel conflicts in the minds of dogs and observing the effect. The logical procedure suggested by his experiments was not taken until almost two generations later. It was reported by TIME magazine, issue of June 8, 1942. During the three years before this date, Jules H. Masserman of the University of Chicago, had made some 200 animals neurotic through developing in them, much as Pavlov had done, powerful mental conflicts. But he did not stop there. After thus developing mental derangement, Masserman restored these animals to normal life. This he did by reconciling the mental conflict which was responsible for the condition.

The harmonizing of the mental factors of one group was accomplished through reassurance and suggestion; of another group through developing pleasure and triumphing over the apparent peril, fear of which was one contending mental factor in the mental conflict; and of the third group by permitting them at leisure to examine the apparatus which had been used to build up the conflict and learn about it for themselves. With sufficient insight into the sequence of things—even as the conflicts within the minds of those who have set unreasonable standards for themselves are reconciled when they get sufficient insight into what they have done, and how it is impeding them—the conflicts disappeared and the animals became normal.

These experiments have a high value not only because they indicate both the cause and cure of much human mental derangement, including that derived from holding to unreasonable standards, but because that which is mapped by a discordant aspect in the birth chart has also been built by conflicts between mental factors. It has been built by the soul in lower forms of life before its birth as a human being.

A discordant aspect maps mental factors in the unconscious which are unreconciled. And these mental factors in conflict work from the inner plane to attract misfortune into the life. They are as blind to the individual’s desires and welfare as were Pavlov’s dogs when they became so crazy they would not touch food, or Masserman’s cats some of which also refused to eat.

When these thought-cell groups within the unconscious mind are harmonized, and no longer frustrated by being opposed by other thought-cell groups, they cease to work to attract events into the life which are at variance with the desires of the individual. And to the extent this harmonizing process is successful will the difficulties mapped in the birth chart and by progressed aspects disappear, and more fortunate events take their place.

Events are the product of the action of thought-cell groups, or mental factors, working from the inner plane to realize their desires, and the resistance of the physical environment to the conditions they strive to bring about. Events of importance come into people’s lives only when there are characteristic progressed aspects present; for only then do special thought-cell groups get enough additional energy to bring to pass the events they want. This energy of progressed aspects also influences the nature of the thought-cell desires, making them more inclined toward events beneficial to the individual if the aspect is harmonious, and more inclined toward events inimical to the individual if the aspect is discordant.

Therefore, even as Masserman found three methods of reconciling the mental conflicts within his cats, so are there three methods through which aspects can be handled. One method is to give the thought cells more harmonious energy with which to work, chiefly through utilizing planetary Rallying Forces. Another is to alter the composition of the thought cells through Conversion or Mental Alchemy. In either of these methods, because the mental conflicts have been reconciled, the thought-cells desire and work for more fortunate events. The third method is to select a type of environment in which the thought cells, whatever their desires, will not have sufficient power to bring to pass the disagreeable event otherwise indicated.

Egotism and Alibis

The child who is brought up in the belief that he is just the smartest thing in the world, under certain circumstances, may never have the unsoundness of this evaluation forced on him by later contacts. As a consequence he continues through life as an egotistical ass. He always has a pronounced opinion about everything, whether he really knows anything about it or not. Once giving out his opinion he clings tenaciously to it. He is the person who never makes a mistake. The mistakes, according to his version, are always made by his associates. What he really needs is to revalue himself, and dissipate the unsound idea built up through his childhood associations.

Those of great knowledge realize that there is enormously much they do not know. They are quick to recognize when they have made an error in judgment and to acknowledge it. Those of sterling ability are the first to admit it when they have made a mistake. But the person who has built up an image of his own perfection may permit it to dominate him. This mental factor may be so strong that it cannot be displaced or influenced by reality. Whatever happens in actual life that is contradictory to this image is warped into conformity with it. He cannot admit, even to himself, that he has made a mistake. His unconscious always invents some fiction by which he escapes from admission of any imperfection. Such an attitude, often quite unconsciously maintained, is always a great obstacle to attaining honors. Other people are not slow to see through such fictions. The truly great man admits his mistakes and profits by them.

Conservatism and Radicalism

Childhood experiences also result in two other pronounced types. We have ever with us the ultraconservative and the radical. The ultraconservative is like a horse which is too severely treated when broken. He has no spirit of his own. He has been taught in early years implicitly to obey his elders without asking the reason why. As he becomes older this unreasoning obedience is transferred to his church, to the traditions of his community, and to everything else that is old and established. The old time religion is good enough for him. The political party of his father is always sound in its platforms. He was taught in regard to all decisions that, “Father knows what is best.” He was never permitted to think for himself as a child, and he will never think for himself as long as he lives unless he is brought to analyze his condition. He will vote as the political boss (a father substitute) dictates, he will believe the Bible from cover to cover in spite of contradictory scientific evidence, and in business he will ever follow established methods and customs. He may attain honors through carrying out old and tried policies, but his influence on society is numbing; for he is a slave to custom and tradition.

At the opposite extreme we have the child who, after a period of coddling is treated in what he considers a very unjust manner. Such unreasonable treatment arouses a strong sense of injustice. This feeling—often due to a childish misunderstanding of his own position which his elders do not take the pains to straighten out—rankles within him until at last it flames into open rebellion. He rebels against father or mother, and is punished for it. This strengthens the emotional content of the image of himself as an unjustly treated individual. As he grows to maturity, because of the strength of this image that the world is against him and everything is all wrong, he comes to be recognized as an individual who, no matter what the topic of conversation, always takes a view in opposition to others.

Later still, out in the world, he fails to get on with people. His associates in work always give him the worst of it. Those who make money are to him grafters. Those who attain honors do so because they have pull. The church is all “bunk,” and the laws of the country are all wrong. Those who work for charity have ulterior motives. He is not wanted anywhere, in truth, because he always stirs up trouble. He is an agitator and a radical not because he compares evidence and deliberates upon it, but because he is still expressing the emotional rebellion built into himself in childhood. If he is to attain any real honor in life he must now dissipate these conditions by recognizing the source of his chronic attitude.

The Precious Child

One of the most common forms of emotional maladjustment arises from too much coddling. The child, because it is told so, or more potent still, because the actions of its parents give it the suggestion, comes to believe it is excessively precious. It is not permitted to do this and to do that because it might get hurt. It must be wrapped up carefully in cool weather to prevent it from taking cold. It must not get its feet wet, or be in a draught. Thus is built into it an overestimation of its own value, and that to preserve such a wonderful creature the thought of safety first should be dominant.

Life and the attainment of honors are an adventure in which initiative and the willingness to undergo hardship and hazard for a worthy cause are essential to success. Nothing so surely defeats worthy aims as undue regard for consequence to self.

Such a coddled child, unless it revalues itself, is never willing to pay the price of success. It cannot bring itself to face the drudgery leading to accomplishment. It is deterred in its progress at every step by fear of consequences to itself. Fear of this and fear of that have so entered its life in early years that it lacks the courage to grasp opportunities as presented. It would like to appear before the world as a wonderful success—for so precious a being as it has always felt itself to be should be looked up to by others—but it shrinks from heavy responsibilities. It actually flees from reality, the reality that lack of courage and willingness to carry the burden is hampering its life. Instead—because the unconscious will never admit anything detrimental to its self respect—the individual invents a thousand and one fictions why he fails to make headway. But he will neither merit nor attain honor until he makes a proper mental adjustment.

If the child has been too much waited on a lack of self-esteem and independence may be carried into adult life. And of even greater detriment the coddling with its resultant self-importance may cause an incurable desire to be in the limelight. The great things of life are accomplished through team work. The child who has not found opportunity to submerge self-interest while cooperating with other children for the common good, at maturity may find itself devoid of one of the greatest assets of life. Real honors come only to those who, when occasions arise, can submerge themselves for the good of a cause. They must always be willing for the other person, if he is better qualified, to fill the post of importance.

Others always perceive the selfishness of the person “who plays to the grandstand” rather than does good teamwork. They resent this attitude, and invariably try to hamper the progress of such an individual.

Inferiority Complex

A very large variety of circumstances may occur in the early years of life to give rise to an inferiority complex. Some real or fancied physical defeat may give a sense of inadequacy. The realization that one’s family is unable to provide one with things possessed by one’s associates. Other circumstances arc: Competition with older children, or with those of superior training, and consequent defeat followed by ridicule; standards of conduct set so high that it is impossible to reach them, and humiliation due to not living up to them; and almost any experience of early childhood accompanied by strong emotions of shame and inefficiency. These give rise to a feeling of inferiority that manifests as an apologetic attitude toward life, as diffidence, lack of self-confidence, hesitancy, and any one of a score of compensating mechanisms.

If the inferiority complex arises from too much coddling he is afraid to try anything that appears difficult because he fears the result to himself. His unconscious has become so firmly convinced of his preciousness that it will not permit him to attempt anything that might bring discomfiture.

Or if, in childhood, he has been compared unfavorably with other children, or has had some experience in which he has felt deep humiliation, the sense of his own preciousness will not permit him to run the risk of repeating the humiliation. He is afraid to talk in public, and is uncomfortable when many people watch him work, because he is afraid he will not live up to the high standards he has set for himself. He might make some mistake before all these people, and the high estimation he has placed upon himself makes this thought unbearable.

Shyness

The unconscious never relinquishes its self esteem. The conscious mind feels inferior, but the unconscious invents countless fictions, makes excuses, runs away from deciding tests, and in all ways attempts to bolster up the idea of superiority.

Early environment sometimes gives the child a greatly overestimated value of himself. In later contact with other children he is unsuccessful in getting them to take him at his own evaluation. They are inclined to ridicule his pretensions of superiority. To associate with them, and enter into their competitions, means a relinquishment of this idea of superiority. Instead of doing this, the unconscious retains the fictitious ideal of self-importance by withdrawing from others. The unconscious feeling of superiority gives rise to a conscious feeling of inferiority. Thus develops the child and finally the adult marked for shyness.

Over Sensitiveness

In a somewhat similar manner the child unduly impressed with its preciousness develops oversensitiveness. He comes to believe himself of greater value than others, and meriting greater care. He is shielded from discord and harshness until he feels such shielding to be his due.

In his actual contact with life he comes in contact with that which is disagreeable. In proportion to the valuation he places on his own welfare, and the protection he has been accustomed to, will these contacts induce fear. Fear always mobilizes the body on a war footing, through causing secretions from the adrenal glands to enter the blood. As a consequence, the adult developing from such a child, or from a child that has had experiences giving rise to fears which through shame or other causes have been repressed, is continually on the defensive. His body is prepared at all times to resist invasion or injury. He is “high strung” and “sensitive” due to an unconscious anxiety. This may be relieved by realizing its cause and tracing it to its childhood source.

Boasting

Boasting and stuttering are always due to a feeling of inferiority. By show and ostentation people unconsciously endeavor to impress others with an importance they do not feel for themselves. The unconscious compensates for the feeling of failure by play acting what it would like to be. Such inferiority may be felt by one who has actually accomplished much, as well as by one who has accomplished little, all depending on the standards. But when a person really feels he has accomplished something worthwhile it gives him a sense of satisfaction, and he is content to rest his case upon its actual merits.

Considerable pains have been taken to point out the origin of those traits of character which more frequently than others prevent people from attaining honors. Some, in spite of outstanding deficiencies, due to other unusual flares, have attained the esteem of nations. But for the most part these we look up to are simple in demeanor, straightforward, sincere of purpose, and without undue overvaluation of themselves.

Edison as a man would not have been so greatly loved in spite of his inventions if he had been egotistical or if he had been unduly diffident. Lindbergh captured the imagination of the world not merely because of his unprecedented flight, but because at that time he did not permit fame to turn his head. Lincoln lives in the hearts of the people as a simple man.

Summary of Emotional Reactions

If you suffer from an inferiority complex, now you have learned its origin, get rid of it by revaluing yourself. Honors are bestowed by people, and people will not place confidence in a person who has no confidence in himself. The suggestion of incompetency that reaches them is too potent. On the other hand, people resent egotism, boastfulness, and too obvious self-superiority. They value themselves by comparison with others. If through mannerisms or dress they get the opinion you look down on them or feel them to be less intelligent, it attacks their self-esteem. This they resent more than anything. The farmers who were really responsible for the election of Lincoln resented the superior polish of Douglas. But Lincoln dressed plainly, always spoke to them as equals, and made them feel that he was one of them.

If you are oversensitive, now you know the cause, take less thought of harshness and annoyances. Too tender a personality is not capable of carrying heavy loads. If you are a chronic kicker, iron that out also. If you are merely a “ditto” mark for the opinions of others, make a few decisions for yourself at once as a start in the right direction, even if these decisions prove erroneous. Cultivate self-reliance. Look upon life as an adventure where taking a few risks is a part of the game. Admit it when you make a mistake. Be willing to acknowledge ignorance when you do not know, and to seek the advice of others who do. Keep ideals always in advance of accomplishment, but beware of setting false standards for yourself. Carry responsibilities when they come your way. We learn to carry heavier loads by first shouldering light ones. Let others have credit for what they do, and they will be more willing to give you credit. Instead of “grandstand” playing enter to the fullest extent into whatever teamwork is necessary to get best results. These are some of the things that help in the attainment of honors.

What Brings Honors

Having thus summed up the more important personal traits leading to public esteem, let us now examine what actions result in the attainment of honors.

We must distinguish between the words “honor,” “fame” and “notoriety.” A notorious person is one who has publicity. The word is commonly used in an unfavorable sense. Thus we speak of a notorious criminal. Fame also implies wide publicity, but not necessarily of a nature favorable or unfavorable to the individual. Honor, however, is esteem due or paid to worth, and honors are the tokens of esteem and respect given by others. Fame may be attained by almost any act that is unique enough to catch the public fancy and give rise to wide discussion. But honors are paid only to those who in some measure render a service to society.

Just a few of the names we honor: Florence Nightingale, largely responsible for the relief of suffering in war time through the Red Cross. Jane Addams, relieving suffering of a different kind through settlement work. Harriet Beecher Stowe whose one supreme literary effort contributed so largely to freeing the slaves. Shakespeare, whose plays have given entertainment to millions, and whose writings have enriched the English language. Newton, whose discoveries made modern engineering possible. Kepler, who widened our universe by discovering some of its laws. Alexander Bell, through whom we have the telephone. Fulton, with his steamboat. Marconi and the radio. Pasteur and immunity from germs. Harvey, discovering the circulation of the blood and adding to our knowledge of physiology. George Bernard Shaw, dramatist and iconoclast, whose keen wit is ever directed against the artificialities. H. G. Wells, who contributes through his books to popular education. We might go on at great length calling to mind every line of constructive endeavor, and we would find that someone had attained honor in it, and invariably that this was due to his contribution to human welfare.

It will be seen, therefore, that honors are not confined to any particular line of effort, but may be attained through any constructive work. It is required, however, that some contribution shall be made to the welfare of men, and that others shall know of this contribution.

It has already been explained in Chapter 1 (Serial Lesson 151) how to find the field of effort where your endeavors will contribute most largely to the Cosmic Work. In this field then, because it is where your greatest abilities lie, is where you will most readily be able to attain honors. It is the field in which your major efforts should be expended.

At the same time, advancement in whatever vocation you may be following should not be neglected. Such advancement, directly or indirectly, is nearly always dependent upon other people. If you are in business for yourself it depends upon those who patronize you, or upon those who work for you, or both. If you do not work for yourself, it depends upon the boss.

Pleasing the Boss

Independence is a fine thing and bootlicking is demeaning. Yet it should injure no one’s self-respect to try to please the boss. It is in his power to promote you or not. Whether he does so depends upon how he feels toward you. Whenever you spare him annoyance, lighten his burdens, and make him feel pleased with himself rather than irritable, you are working in the best interests of the firm, and toward promotion for yourself.

Every boss has peculiarities. He has his good days and his bad days. He overreacts emotionally to certain situations. If you are observing you will learn these things. And you will not ask favors on those days when, for instance, his demeanor shows that he has just come from a domestic ruckus. Certain sore spots, although they may seem unreasonable, you will learn to avoid entirely. This is not being a sycophant; it is learning how to handle your job so that the boss will be better able to do his work.

Prepare to Fill a Better Position

The only way you will ever get to the top is by shouldering responsibility. Whenever possible, therefore, relieve your superior of some duty. He will appreciate this, you will learn how to perform the duty, and when there is need for someone to perform this or some higher work you will be the first person thought of. Carry as much of your boss’ responsibilities as he will let you and that you can handle. Advanced positions are filled from those who have a background of experience.

Each position and each line of endeavor have their own peculiar requirements. Make a thorough analysis of the qualities and habits needed to fill the job you now perform, and of the habits and qualities needed to fill the job in advance of the one you now hold.

A singer of my acquaintance some years ago undertook the added labor of learning twelve songs in the German language because some day she hoped to sing in the capitols of Europe and perhaps Berlin would be among them. Shortly after, a director wished to fill an important engagement in Berlin with an American singer. There were a number to choose from, but these asked for several months to learn the songs and he needed a singer in a hurry. My acquaintance, who had a dozen such songs ready for recital, thus got the chance of her lifetime, and went on from there to greater heights. She was prepared, by doing what seemed unnecessary work, for almost any engagement that might offer.

You cannot know too much about your work. Read everything you can get that has a remote bearing on it.

But the most important thing of all is your habit systems. After making a careful survey of the habits that conduce to getting ahead, start in, one at a time, to cultivate them. The more important emotional reactions that hamper advancement, and how to readjust them, have already been mentioned. One of the habits you will need is that of determination of purpose. Get a clear idea of what you desire to accomplish and let nothing deter you from reaching this end. Such a course means the cultivation of will power. But in addition to such obvious traits there are numerous others that you will be able to think of, some that detract from and some that conduce to the attainment of success in your particular work.

Character

The foundation for the attainment of honors is character. And character is the sum total of the habit systems. In the development of character, and in the efforts to advance your work, in some manner cultivate strong desires to do the proper things. These desires will direct the imagination to the image of doing the thing, instead of to the image of not doing it. Thus will and imagination will pull together. When they pull in opposite directions imagination always wins. Dr. Coué formulated this nicely by stating that whenever there is a conflict between the imagination and the will, the power exerted by the imagination is as the square of the power exerted by the will. The stronger the will, the more energy drained into the mental image; for the imagination, in such conflict, is always victorious.

The character, built up to cope with such problems should be energetically engaged in such enterprises as will benefit others. In every community there is opportunity to perform a public service. In every group there is an opening to further the ends of the group. The successful fulfillment of one responsibility opens the way to the acceptance of another. Everywhere there are worthwhile things that need to be done if someone will but make the sacrifice to do them.

Yet doing something worthwhile does not confer honors unless people know about it.

Advertising

Advertising one’s accomplishments and virtues unduly is certainly bad taste and does not conduce to honors. On the other hand, undue reticence detracts from one’s opportunities to render public services in the future. If one has ability, or if one has accomplished something, there are inoffensive ways by which others may be made aware of it. In other words, the attainment of honors requires in addition to other things, a certain amount of delicate salesmanship.

In such salesmanship, as in all others, the first thing is to attract the attention of the prospect. In this case the public, the boss, or the group of which you are a part. Ingenuity probably will need to be exercised in this so as to make the contact and hold the attention without alienating. In some way keep the boss, or group, or public, interested in your accomplishments. To do this study the individual or individuals by whom you wish to be noticed. Learn what they are interested in and link your work in some way to these interests.

They may not know what they need, but if they suspect that you are trying to dictate what is good for them they will resent it as an impertinence. It is often necessary to give what is good for them together with the things they already are desirous of having in order to get the former accepted. This is not disparaging the boss or the public; it is utilizing the same principle that you use in building into yourself new habit systems.

The attention having been attracted and held, you must use it as an opportunity to build up the desire for the thing you are doing. Not only is it impossible to gain honors, but it is difficult to do much of anything for others unless by some means you can arouse their desires for the service you are performing. If you make yourself both agreeable and useful, the boss will desire your services. If you can convince the public that they are benefitted through your efforts, they will desire these services to continue.

Occult Considerations

The first thing, in seeking honors, is to find in what field it is possible for you to attain them. Past performance is some gauge of where you can use ability to gain recognition; but nothing else is the equal in this respect to an analysis of the birth chart. This will indicate where your efforts may be directed so that the public will receive most benefit and you will receive most favorable notice.

The progressed aspects also afford the best map obtainable of what you may reasonably expect to accomplish at any given time. This does not mean that there are times when you should merely drift. It signifies that at some periods the efforts directed into certain channels would be quite futile to bring anything but misfortune, but that at the same time efforts directed in other ways would advance you somewhat toward your chosen goal.

Whatever your goal may be you need no special aspects by progression to enable you to work toward it. Every day of every year, for instance, may be utilized, in spite of astrological or other conditions, to build character. And honors rest largely upon character. But under some astrological influences you will be able to make strides in a given direction that would be quite impossible under other astrological influences.

The work leading to honors may be accomplished gradually, and under various astrological conditions; but the most favorable time for receiving the honors is when there is a favorable major progressed aspect to the ruler of the tenth house of the birth chart, and at the same time a progressed aspect to the Sun. Such a time may especially be utilized to bring to the notice of others what you have done or what you are capable of doing.

When the Sun is making afflictions by major progressed aspects it is unusually difficult to get proper recognition from superiors, and when there is no major progressed aspect to the ruler of the tenth house there is little likelihood of promotion.

The strongest thought cells in your astral body for influencing honors are mapped by the ruler of the tenth house. Therefore you should cultivate those thoughts which most powerfully will give these thought cells strong harmonious vibrations. If they are discordant, as shown by the birth chart, a mental antidote, as explained in Course IX, Mental Alchemy, should be applied to change the discord into harmony. But in any case such thoughts should be cultivated in association with the things ruled by this planet that the vibrations of these honor-attracting thought cells will be greatly and harmoniously increased.

The honor-attracting thought cells within you may also be intensified by associating with objects having the same planetary ruler (Course VI, Sacred Tarot). But such objects should not be chosen as associates unless the thought cells are harmonious. If they are shown to be discordant, you should instead choose the locality, house number, telephone number, color, gem and signature that vibrates to the planet aspecting the ruler of the tenth house most favorably.

Demonstrating Honors

You should have a clear idea of just what you wish to accomplish, or at least the next step or two ahead in its direction. To enlist the aid of the unconscious mind and its tremendous powers in this attainment, visualize frequently, and as clearly as you can, yourself as you would appear in the attainment of your ambition. Hold this image, feel confident it will be realized, and repeat: THIS I AM NOW ACCOMPLISHING.

Birth Charts

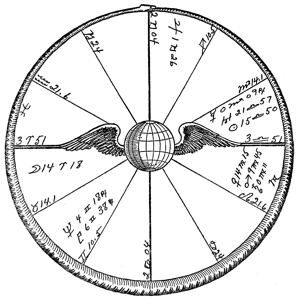

General Eddie Rickenbacker Chart

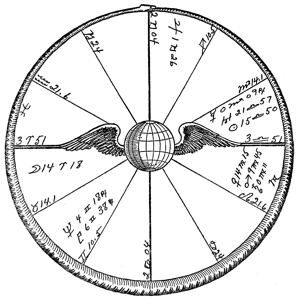

October 8, 1889, 4:58 p.m. LMT. 83W. 40N.

(Data given by mother to Colonel Frank E. Noyes.)

1917, overseas as member of General Pershing’s Motor Car Staff, two months later transferred to Air Service: Mercury semisquare Mars r, Venus sesquisquare Neptune p.

1918, Commanding Officer 94th Aero Pursuit Squadron which shot down 69 planes, 26 to Rickenbacker’s personal credit: Mercury semisextile Mars p, Sun sextile Venus r.

1922, married: Mercury sextile Saturn p.

1928, organized Rickenbacker Motor Co.: Mars trine Neptune p.

1943, on special military mission was forced down in Pacific, given up for lost was found 21 days later after one of the seven men with him had died of thirst and exposure: Uranus semisquare Mars r, Sun semisquare Uranus p.

|

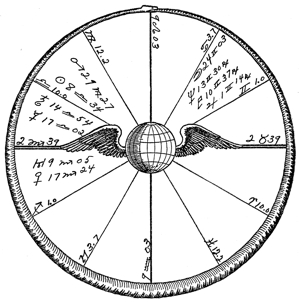

Faith Baldwin Chart

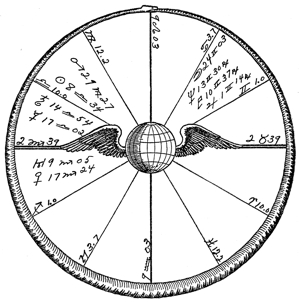

October 1, 1893, 8:00 a.m. 74W. 41N.

(Data furnished by her to a Hollywood astrologer.)

1920, Nov. 10, married: Venus sextile Saturn p, Moon sesquisquare Sun p.

1921, first book, Marvis of Green Hill, published: Mars conjunction Mercury r.

1923, under difficulty wrote Laurel of Stony Stream: Mars conjunction Saturn p.

1924, published Magic and Mary Rose: Sun conjunction Uranus r.

1925, wrote two books: Sun parallel Uranus p.

1926, started a decade in which she had published one or two books a year: Sun conjunction Uranus p.

1936-37, her most brilliant writing, Manhattan Nights: Mars sesquisquare Neptune r and p.

|

|

|